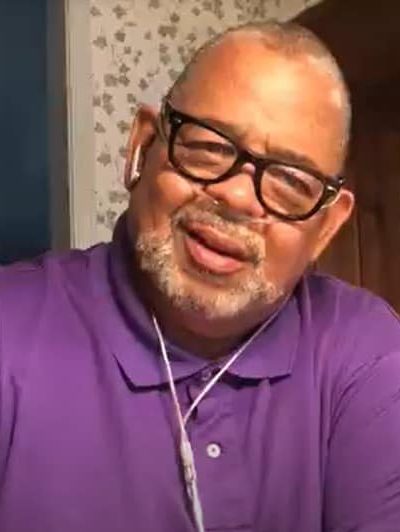

Forced to breathe at times through oxygen tubes, the Rev. Kevin Goode nonetheless counts his blessings. Although his lungs are scarred from asbestos exposure and he has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he’s in better condition than other former employees of rubber factories in Akron, Ohio.

Goode, retired pastor of Church of the Harvest, worked 15 years for the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. For most of that time, he tested the characteristics of competitors’ tires in a lab while other employees built new tires below. He didn’t think much about the asbestos, chemicals and soot inside the building, or the black clouds billowing from smokestacks around the Rubber Capital of the World.

“The stuff was everywhere – in your pores, on your skin,” Goode recalled of the lamp black, also known as carbon black, which added sturdiness and color to the tires but can cause skin conditions, cancer, respiratory problems and cardiovascular disease. “You take a shower, you blow your nose or if you cough up phlegm, it was always black.”

Goode, 64, started at the factory in 1975 when he was 17. “You’re young and you think you’re invincible, but you knew it had an impact,” he said of his exposures.

“We just knew something was not healthy about it, but nobody did anything. We were glad to take the paycheck.”

Goode is among thousands of people in the Akron area who have received workers’ compensation benefits, class-action settlements or payments from personal-injury lawsuits against tire manufacturers, their subsidiaries and their suppliers. Their ailments range from asbestosis to cancer.

Without these lawsuits – along with pressure from labor unions and regulators – the rubber companies would have done little to address health issues, many in Akron say. “Back in the day, they used to fight us tooth and nail,” said Jack Hefner, immediate past president of Local 2L of the United Steelworkers union, which absorbed the United Rubber Workers.

“How many people died early and unnecessarily from benzene and toluene and asbestos and soapstone and lamp black?” asked Hefner, a third-generation union official who spent 10 years at General Tire until it closed in 1982 and recently retired from Maxion Wheels USA LLC, formerly the old Goodyear rim plant.

“We just knew something was not healthy about it, but nobody did anything. We were glad to take the paycheck.”

Rev. Kevin Goode, worked 15 years for the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.

None of the remaining rubber companies contacted for this article would discuss specific details on their industrial hygiene and environmental practices over the years. Among the Big Four, General Tire was sold to Continental, and B.F. Goodrich no longer exists (though tires are still sold under both brand names). Firestone declined to comment, and Goodyear provided a written statement.

“We have policies and procedures in place focused on material handling and the safe use of substances used or stored at our facilities,” Goodyear stated. “Preventing work-related illness in the workplace begins with understanding the potential impacts of noise and the substances used in the manufacturing process. We assess workplace exposures through monitoring, which validates that controls are effective and provides transparency to associates.”

The rubber industry, which began in Akron in the early 1870s, has exposed its workers and neighbors to an array of poisons. But two stand out: asbestos and benzene. The former is a fibrous mineral known for its fire resistance. The latter is a natural constituent of crude oil used as a solvent for decades. Both can do severe damage to the human body.

Asbestos floating like snowflakes

Goodyear and other rubber companies in Akron began insulating their tire factories with asbestos and using it in manufacturing at least as far back as the early 1900s, sold on the mineral’s malleability and imperviousness to chemicals, heat, electricity and water. One of their suppliers was the Johns Manville Corp., the nation’s leading maker of asbestos products for a half-century.

The Summit County Court of Common Pleas in Akron became a hotbed of asbestos litigation, fielding thousands of claims filed against Johns Manville by workers suffering from lung cancer or other asbestos-related diseases – or, because many have died, their heirs. Since 2015, more than 2,000 of these cases have been settled, the claimants paid from an $80 million national trust fund established by Travelers, Johns Manville’s largest insurer. But the settlement amounts have been modest – as low as $800 and rarely more than $20,000, said Thomas W. Bevan, an attorney based in Hudson, Ohio.

“The shame of it is that the families wait a very long time for a very small amount of money,” said Common Pleas Judge Elinore Marsh Stormer. “You want to see justice being done. And I don’t know that waiting 20 years for $1,200 is justice.”

Johns Manville filed for bankruptcy in 1982 to avoid what it called “tremendous liability” from the rush of lawsuits after the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, known as OSHA, began regulating asbestos. Plaintiffs went after the company’s insurers following the Chapter 11 filing; the bankruptcy court approved a multimillion-dollar settlement with Travelers in 1986. Johns Manville emerged from Chapter 11 in 1988, but nearly three decades of litigation continued. Some later plaintiffs not included in the 1986 settlement accused Travelers of misrepresenting Johns Manville’s and its own knowledge of asbestos hazards.

Tied up by appeals, the case eventually reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 2009. The justices remanded the case to an appeals court, which in 2014 reinstated a bankruptcy ruling that Travelers pay settlement agreements and interest totaling $500 million.

“This was an extremely unusual case,” said Bevan, who cut his legal teeth as an asbestos litigation law clerk in 1989, assisting a mentor with lawsuits against rubber companies he says no one wanted to take because of their difficulty. In his first case out of law school in the early 1990s, he represented a Goodyear employee with lung cancer who had been exposed to asbestos.

“The initial stance was complete and total denial, like this was some type of a hoax or scam,” he said of Goodyear. A company lawyer, Bevan said, “pounded his fist on the table and said, ‘We’re a tire company; we don’t use asbestos!’ … They had an asbestos department there at Goodyear. I’ve got pictures of it.”

“They laughed in my face, literally,” Bevan said. “They guaranteed that they would win the case. … After a two-and-a-half-week trial and they lost, they were like: ‘Wait a minute. We have a problem here.’”

Bevan, whose parents worked briefly at tire companies, said one of the saddest of the 15,000 asbestos cases handled by his firm involved a retired Goodyear electrician who sold everything to buy a boat to sail around Florida and the Caribbean. “That was his dream for many years, and then he began to have these breathing problems.” He had mesothelioma, an aggressive, asbestos-related cancer that can affect tissue lining the abdomen, lungs, heart or testicles. After his diagnosis, he sold his boat and rented a trailer in Florida.

“I went down to meet with him prior to giving a deposition,” Bevan said. “This big, strong, proud, tall guy was just like a skeleton. The cancer was so bad that he had to urinate about every 10 minutes. He had a Porta Potty right there in the trailer next to the chair where he was sitting. He apologized ahead of time because the medication and the cancer were affecting him. He said, ‘I hope you don’t mind.’”

“After a couple of hours, he just couldn’t make it and urinated on himself,” Bevan recalled. “You could see the look on his face — the humiliation and the embarrassment and what this disease had done to him.”

In his litigation, Bevan used the photos that had accompanied the lead article in a 1964 issue of Goodyear’s newsletter, marking the 50th anniversary of the company’s Asbestos Industrial Products Division. The photos show workers with no respiratory protection handling asbestos — from refining the fiber at the loading bin to rolling up sheets of asbestos for shipment.

Former employees at rubber companies throughout Akron describe asbestos floating inside plants like snowflakes and coating their skin and clothing with white dust.

Asbestos was in the plaster that Nathan J. Manson used to make molds for tires at Goodyear from 1976 to 2005. Manson, who also served as a supervisor, developed breathing problems during that time and was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, known as COPD, about 10 years after he retired. He didn’t attempt to sue Goodyear, even though he believes his condition is related to his work there.

“Now that I’m getting older, my COPD is getting bad,” says Manson, who needs oxygen twice a day, uses inhalers and had a stroke three years ago. The 77-year-old loved fishing on Lake Erie, but ended up selling his boat. Though he still grows green beans, squash, zinnias and especially marigolds in his garden, “I tell everybody, I work for five minutes; then I have to sit down for 15.”

The benzene connection

Beginning in 1934, Goodyear began making Pliofilm, a rubberized plastic used to protect equipment and weapons as well as to wrap food and drugs, at plants in Akron and St. Mary’s, Ohio. Workers used benzene, a solvent first linked to leukemia and other blood cancers during the late 1940s, in the manufacturing process.

Peter Infante, then a young epidemiologist with the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, or NIOSH, was among the first to spot the risk to Pliofilm workers. His first study, published in 1977, showed a five- to tenfold increase in the risk of leukemia among workers heavily exposed to benzene from 1940 through follow-ups on their status in 1975.

Immediately after the study was published, OSHA said it would consider an emergency temporary standard for benzene, tightening the exposure limit from 10 parts per million to 1 ppm, thought to be the lowest feasible level. Marvin J. Sakol, an Akron hematologist featured in the study, testified at OSHA’s benzene hearing in Washington on July 20, 1977.

Sakol had treated a number of rubber employees, diagnosing nine of 120 Pliofilm workers with acute erythroleukemia, or Di Guglielmo’s Syndrome, a rare form of cancer. “I became suspicious because they all worked in the same department,” Sakol testified. “Nine people can’t get Di Guglielmo’s out of 120 unless there is something in the environment, work environment, doing it.”

When he started asking questions, Sakol said, Goodyear’s medical director told him “to keep my nose out of it and that was none of my business.” The company denied at the time that the Pliofilm workers had been exposed to benzene.

When OSHA moved to make the 1 ppm benzene standard permanent in 1978, it was sued by the American Petroleum Institute and other industry groups that argued the number was unattainable and would cripple business. In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in their favor, saying the government hadn’t proved that the benzene limit should be lowered. Not until 1987 did the 1 ppm limit take effect.

Infante, who worked at NIOSH and then OSHA before becoming a plaintiff litigation expert, says that standard is obsolete. “Europeans are recommending a benzene exposure limit of 0.05 ppm – 20 times lower than the U.S.,” he pointed out.

Decades of evidence

“The rubber industry was full of cancer-causing agents,” said Hefner, the local union leader. “They knew benzene was bad. They knew asbestos was bad. I mean, these companies aren’t stupid, but they refused to do anything about it.”

For example, in the published proceedings of the 28th National Safety Congress in 1939, Goodyear physician Dr. P.A. Davis wrote about “Dusts in the Rubber Industry,” including lung conditions such as asbestosis and silicosis. Davis acknowledged that “all dusts are detrimental in the human system as a whole when the concentrations are high enough.”

Infante said such evidence has been available to companies for more than a century in some cases, citing 1897 Swedish research on the association between benzene and blood disorders.

“We had the first cases of leukemia reported in 1928 in Italy,” he said. “The companies had information, I would say, by the ’50s.”

For example, Shell was aware of the connection between benzene and leukemia through a 1943 report prepared for the company and a 1950 memo from a consultant.

“Workers were dying not only from aplastic anemia, or to what we call pre-leukemia, but they were also dying from leukemia. And [companies] just sat on it; they didn’t want to affect their business,” Infante said. “And then when the workers would get leukemia, they would deny it, because they didn’t want the public to know.”

While much has changed, internal company memos and other documents dating to the early 1900s indicate that companies throughout the rubber ecosystem were not only aware of the dangers of various chemicals, such as asbestos and benzene, but that some also attempted to conceal the risk these substances posed, as Sakol indicated in his testimony about the blood screenings his leukemia patients received at the rubber plants.

“When we made the site visit in ’76, some of our staff pointed out to us that some folders for the Pliofilm workers were empty, and it seemed suspicious at the time,” Infante recalled.

At Babcock & Wilcox, which supplied many rubber companies with boilers and other products containing asbestos, a memo among eight managers in 1978 suggested quietly fixing violations in its Electrode Shop but not posting warning signs or notifying employees and OSHA about excess dust of “suspected carcinogens [such] as asbestos, iron powder, silica flour and others.”

“The investigation is going to be handled as discreetly as possible,” the memo stated. “It is a concern of the meeting attendees that a labor problem such as a walkout or an OSHA citation for noncompliance would be forthcoming if the hourly labor force was aware of the apparent danger of asbestos exposure.”

BWX Technologies Inc. and Babcock, its former parent company, both declined to comment on the memo.

But across the industry, workers had already realized something was wrong. Union leaders negotiated with six major rubber companies to fund health studies on the work environment during the 1970s that resulted in landmark research by Harvard University and the University of North Carolina.“There was consensus between the union and the companies that members were contracting and dying of cancer at a pretty high rate,” said David Goldsmith, an epidemiologist at George Washington University who was part of UNC’s research team and later led a study on prostate cancer among rubber workers.

“Both sides knew that it was a severe issue,” Goldsmith said. “There was clearly a meeting of the minds that in other contexts might have pushed the union and the companies in opposite directions.” With access to company, union and death records, the researchers were able to study specific jobs and their chemical exposures. They diagnosed illnesses among workers in those areas.

Bevan, the plaintiff attorney, said people who didn’t work in the plants also faced damaging exposures – cases that are harder to win. “Some people got the exposure because a family member brought it home on their clothes,” he said. Chemical residue can also collect on workers’ hair, under their nails or in their pores.

Several medical studies have associated cancer, respiratory conditions, neurological problems and autoimmune disease with take-home and environmental exposures, ranging from asbestos and benzene to neurotoxins that affect the brain and endocrine disruptors such as lead that disrupt neurodevelopment in children. Some chemicals are also transmitted genetically or through transplacental exposure. “For pregnant women exposed to benzene, their children have a higher risk of developing leukemia,” Infante said.

“There was consensus between the union and the companies that members were contracting and dying of cancer at a pretty high rate.”

David Goldsmith, an epidemiologist at George Washington University

The widow of one of Sakol’s patients developed erythroleukemia after washing her husband’s benzene-saturated overalls night after night for at least two decades. She fought seven years to secure workers’ compensation for her husband’s death, and she died less than a year later, Infante said. “She was never able to get any remedies for her own illness.”

One couple, who lived on the edge of the Industrial Excess Landfill, a Superfund site in Uniontown, Ohio, settled out of court with the potentially responsible parties after their 21-year-old son died of bone cancer. Rubber and other companies dumped tons of solid and liquid waste at the landfill. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently began an investigation of groundwater contamination in the area.

Although many rubber workers and residents have sought compensation for illnesses associated with industrial chemicals, untold numbers of people didn’t try, or it never even crossed their minds.

Dawn Kupris Phifer suspected a rubber industry connection to cancer and other illnesses suffered by relatives and classmates over the years. Phifer grew up in Goodyear Heights, a factory neighborhood. Her father, grandfather, brother, two sisters and son all had cancer. Some family members and friends dismissed her concerns or told her she was being negative, she said. This isn’t unusual given the strong city pride and nostalgia for the Rubber City days.

Norma James’ family also never considered any legal action for their ailments. Her father worked at Goodyear and was diagnosed with lung and prostate cancer. Her mother had uterine cancer. Her uncle, a Goodyear employee who lived less than a mile from company headquarters, had prostate cancer, and his wife had brain cancer.

James, who has asthma, said her father usually showered at the plant. When he’d wear his work clothes home, he’d remove them in the garage. “He talked about washing his hands and using acetone and benzene to clean himself,” she said. “The doctors later said that the years of doing that could have contributed to his cancer.”

Preston Andrews suspects that disproportionate exposure to lamp black, benzene and asbestos played a role in the deaths of his father, a Goodrich employee, and an uncle, a Firestone worker. The elder Andrews and his siblings grew up in a tiny village in Louisiana and migrated one by one to an apartment building near Goodyear in East Akron during the 1940s, as word spread of opportunities at the rubber factories and an escape from harsher forms of racism in the Deep South. As in other industries, African Americans were relegated to “occupational ghettos” in the lowest-paying, dirtiest and most dangerous jobs — work at the front end of production that exposed them daily to a greater share of toxic chemicals, which clung to their clothes and spread to their families.

“When my dad and them first started, they basically worked in the mill room,” Andrews said, describing tasks mixing raw rubber with lamp black and other chemicals. “They couldn’t build tires.” Andrews, who worked at B.F. Goodrich from 1966 until he was downsized in 1981, believes that he might have fared better than his elders, because he spent only two years in the mill room after his father helped him land a job in the hose room.

“It was clear that there were specific job patterns,” Goldsmith, the epidemiologist, said of the UNC and Harvard research findings. “African American men started at the dirtiest jobs like compounding and mixing.”

Manson, who was active in the union, said opportunities and conditions started to improve by the time he and Andrews settled in as rubber workers, the result of union pressure, civil rights legislation and industrial regulations. Pay increased in the mill room, he said, and the pool of workers became more integrated.

“The rubber shop started making amends and loosening up because they didn’t want walkouts and sit-down strikes,” Andrews added. “They needed the tire supply.”

Remedies through regulations

The Cuyahoga River — polluted with rubber waste that flowed north from Akron, poisons from Cleveland industry and cars, tires and mattresses dumped there — caught on fire more than a dozen times before the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972. It became a symbol of rising environmentalism against a backdrop of deindustrialization. A growing interest in health and environment that began in the 1960s culminated in a flurry of new regulatory agencies and regulations in the 1970s.

Workers and the public saw gradual improvements, though change came too slowly for many, including Gary Clark’s father and grandfather, both of whom died of lung cancer and worked at tire companies. Clark, who joined his father at Goodrich during the late 1970s and worked there for seven years, benefited from more protective gear and safer conditions under the new laws.

But he couldn’t escape the lamp black, which seeped from his pores, irritating his skin and staining sheets. Clark said that it took him a month to adjust to the intensity of the sulfuric stench: “That smell is times 100 once you walk into the plant.”

The laws themselves were not without defects. For example, the Toxic Substances Control Act, known as TSCA, didn’t cover tens of thousands of legacy chemicals that were automatically deemed to be in compliance with testing requirements. Fewer than a dozen chemicals have been banned under TSCA since it took effect in 1976.

Not until 2019 did the EPA announce that it would start risk evaluations of asbestos, Trichlorethylene (TCE), 1,3-Butadiene and formaldehyde, all of which have been used in the rubber industry.

OSHA, for its part, has been unable to keep pace with the glut of hazardous chemicals in the workplace. In an unusually candid public statement in 2013, the agency’s then-leader, David Michaels, said, “There is no question that many of OSHA’s chemical standards are not adequately protective.” As a result, OSHA said, “tens of thousands of workers are made sick or die” from chemical exposures.

“There is no question that many of OSHA’s chemical standards are not adequately protective.”

David Michaels, then-head of OSHA

Environmentalists are cautiously optimistic about the future under the Biden administration, which has moved to increase corporate responsibility for Superfund cleanups and reduce the backlog, among other initiatives.

“We’re going to have to wait probably about 24 months into this administration to see if they’re really serious,” said Mustafa Santiago Ali, vice president of environmental justice, climate and community revitalization at the National Wildlife Federation. Ali spent 24 years with the EPA, most recently as senior adviser for environmental justice and community revitalization.

The way forward

In Akron, the remaining rubber plants are much safer than in years past, though smaller with the end of passenger tire production between 1975 and 1982. Both Goodyear and Firestone still produce racing tires in the Rubber City.

On the corporate level, Goodyear has been experimenting with renewable materials such as soybean oil, which has replaced petroleum in some of its recent tire lines, as well as substitutions for lamp black. Firestone’s parent company is using recovered lamp black from recycled tires to reduce carbon emissions.

Overall rankings for Goodyear, the world’s largest tiremaker, have improved on the Toxic 100 lists released by the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Goodyear is now 71 on the 2021 Toxic 100 Air Polluters Index, down from 19 in 2008. Bridgestone/Firestone, 81 in 2008, was off the list entirely last year.

Now that most production has shifted south, west and overseas, Akron plants account for less than 5% of their parent companies’ toxic scores.

But delays in controlling emissions inside and outside the plants will have long-lasting consequences, said Stephen Markowitz, director of the Barry Commoner Center for Health and the Environment at Queens College in New York, who has consulted with NIOSH and the EPA.

“Safer conditions in the last 10 years won’t be reflected in health … for another 20 or 30 years,” said Markowitz, who co-authored a 1991 study linking ortho-toluidine to bladder cancer at Goodyear Chemical in Niagara Falls. And while less pollution is spewing from the factories’ stacks with deindustrialization, toxic chemicals from the past are everywhere. “A lot of soil contamination really sits around for years and years and even decades,” Markowitz said. If the soil is disturbed – say, by construction or children playing – those chemicals can become airborne.

The way forward for citizens is to become more educated about the impact on their health, to push for corporate responsibility, to vote and to improve regulations, policies and funding at the local, state and national level, Ali said.

“We have to make sure there’s more transparency in all of these processes and the systems,” he said.

Akron is slowly coming back from its industrial past, continuing attempts to diversify its economic base, clean up symbols of industrial pollution such as Summit Lake, honor rubber workers with a new downtown monument and redevelop brownfields — the empty facilities and land left behind by rubber companies.

Jason Segedy, the city’s director of planning and urban development, sees brownfield redevelopment as a win that stimulates economic growth and cleans up potentially hazardous areas.

Akron had 75 brownfield sites in an initial inventory, according to the EPA. Two-thirds of the sites are part of three projects in areas with above-average poverty and unemployment rates: Riverwalk, where Goodyear’s new headquarters is located; the Bridgestone Redevelopment Area, which includes Firestone; and the Biomedical Corridor, south of Goodyear and east of Goodrich. The sprawling Goodrich campus now includes a park, business incubator and Spaghetti Warehouse.

A plan to re-envision Summit Lake has captured wide attention. Some Akron residents have fond memories of the lake as a tourist destination with an amusement park, dance hall, skating rink, beach and pool. Located about two miles from downtown, the 97-acre natural lake was once a source of drinking water, but eventually became so polluted with industrial waste from rubber factories and other companies that the city quit using it for that purpose and banned swimming there.

City leaders have been meeting with residents of the long-neglected Summit Lake community to solicit their input on neighborhood and recreational improvements, update them on water quality and attempt to squash gentrification concerns. Firestone’s old pump house there is now a nature center.

Summit Lake is symbolic of how much cleaner Akron has become, said John A. Peck, a professor in the Department of Geosciences at the University of Akron. For a long time, the magnetic and heavy metal content of the lake’s sediment grew along with the rubber industry and the city’s population.

“It skyrocketed, and it stayed high for a long time,” Peck said. With each passing year, cleaner sediment buries contaminated sediment, but “you know not to go dig it up.”

“The cool thing to me about Summit Lake is that in the center of an urban setting, you have this natural jewel,” Peck said.

Memories of the sulfuric odor from factory smokestacks still draw debates on whether it was the smell of money and prosperity or of disease and death. Considering the past and future costs, was it all worth it?

There are no easy answers. Without the rubber industry, said residents from Europe, Appalachia and the Deep South, they wouldn’t be who they are or where they are. Akron wouldn’t be Akron.

For the Rev. Kevin Goode, often reliant on oxygen tubes to breathe, counting his blessings doesn’t mean he has no regrets.

“In retrospect, looking back,” Goode said, “I probably wouldn’t have worked where I worked.”

This article first appeared on Center for Public Integrity and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

====================================

Postiamo una traduzione in italiano effettuata con google translator per facilitare la lettura dell’articolo .

Era la capitale mondiale della gomma. Le conseguenze sulla salute permangono.

Questa è la terza e ultima puntata di una serie pubblicata da Belt Magazine in collaborazione con il Center for Public Integrity nell’ambito di una sovvenzione del Fund for Investigative Journalism. Yanick Rice Lamb è stato anche un National Press Foundation Cancer Issues Fellow e un National Cancer Reporting Fellow attraverso il National Institutes of Health e l’Association of Health Care Journalists. Può essere contattata a ylamb@howard.edu.

Costretto a respirare a volte attraverso tubi di ossigeno, il reverendo Kevin Goode conta comunque le sue benedizioni. Sebbene i suoi polmoni siano segnati dall’esposizione all’amianto e abbia una broncopneumopatia cronica ostruttiva, è in condizioni migliori rispetto ad altri ex dipendenti delle fabbriche di gomma ad Akron, Ohio.

Goode, pastore in pensione della Church of the Harvest, ha lavorato 15 anni per la Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. Per la maggior parte del tempo, ha testato le caratteristiche degli pneumatici della concorrenza in un laboratorio mentre altri dipendenti hanno costruito pneumatici nuovi sotto. Non pensava molto all’amianto, ai prodotti chimici e alla fuliggine all’interno dell’edificio, o alle nuvole nere che fluttuavano dalle ciminiere intorno alla capitale mondiale della gomma.

“La roba era ovunque – nei pori, sulla pelle”, ha ricordato Goode del nero lampada, noto anche come nerofumo , che aggiungeva robustezza e colore agli pneumatici ma può causare malattie della pelle, cancro, problemi respiratori e malattie cardiovascolari. “Fai la doccia, ti soffi il naso o se tossisci catarro, era sempre nero.”

Goode, 64 anni, ha iniziato in fabbrica nel 1975 quando aveva 17 anni. “Sei giovane e pensi di essere invincibile, ma sapevi che ha avuto un impatto”, ha detto delle sue esposizioni.

“Sapevamo solo che qualcosa non era salutare, ma nessuno ha fatto nulla. Siamo stati felici di prendere la busta paga”.

Goode è tra le migliaia di persone nell’area di Akron che hanno ricevuto indennità di compensazione dei lavoratori, accordi di azioni collettive o pagamenti da cause per lesioni personali contro produttori di pneumatici, le loro filiali e i loro fornitori. I loro disturbi vanno dall’asbestosi al cancro.

Senza queste cause legali, insieme alle pressioni dei sindacati e delle autorità di regolamentazione, le compagnie di gomma avrebbero fatto ben poco per affrontare i problemi di salute, dicono molti ad Akron. “In passato, ci combattevano con le unghie e con i denti”, ha detto Jack Hefner, immediato past presidente del Local 2L del sindacato United Steelworkers, che ha assorbito la United Rubber Workers.

“Quante persone sono morte prematuramente e inutilmente a causa del benzene e del toluene e dell’amianto, della pietra ollare e del nero della lampada?” ha chiesto Hefner, un funzionario sindacale di terza generazione che ha trascorso 10 anni alla General Tire fino alla sua chiusura nel 1982 e recentemente si è ritirato da Maxion Wheels USA LLC, ex fabbrica di cerchi Goodyear.

“Sapevamo solo che qualcosa non era salutare, ma nessuno ha fatto nulla. Siamo stati felici di prendere la busta paga”.

IL REV. KEVIN GOODE, HA LAVORATO 15 ANNI PER LA GOODYEAR TIRE & RUBBER CO.

Nessuna delle restanti aziende di gomma contattate per questo articolo discuterà dettagli specifici sulla propria igiene industriale e pratiche ambientali nel corso degli anni. Tra i Big Four, la General Tire è stata venduta a Continental e BF Goodrich non esiste più (sebbene gli pneumatici siano ancora venduti con entrambi i marchi). Firestone ha rifiutato di commentare e Goodyear ha fornito una dichiarazione scritta.

“Abbiamo politiche e procedure in atto incentrate sulla movimentazione dei materiali e sull’uso sicuro delle sostanze utilizzate o immagazzinate presso le nostre strutture”, ha affermato Goodyear. “La prevenzione delle malattie professionali sul posto di lavoro inizia con la comprensione dei potenziali impatti del rumore e delle sostanze utilizzate nel processo di produzione. Valutiamo le esposizioni sul posto di lavoro attraverso il monitoraggio, che convalida l’efficacia dei controlli e fornisce trasparenza ai dipendenti”.

L’industria della gomma, iniziata ad Akron all’inizio degli anni ’70 dell’Ottocento, ha esposto i suoi lavoratori e vicini a una serie di veleni. Ma ne spiccano due: amianto e benzene. Il primo è un minerale fibroso noto per la sua resistenza al fuoco. Quest’ultimo è un costituente naturale del greggio utilizzato da decenni come solvente. Entrambi possono causare gravi danni al corpo umano.

Amianto che galleggia come fiocchi di neve

Goodyear e altre società di gomma ad Akron iniziarono a isolare le loro fabbriche di pneumatici con l’amianto e ad utilizzarlo nella produzione almeno fin dai primi anni del 1900, vendendo grazie alla malleabilità e all’impermeabilità del minerale ai prodotti chimici, al calore, all’elettricità e all’acqua. Uno dei loro fornitori era la Johns Manville Corp., il principale produttore nazionale di prodotti di amianto per mezzo secolo.

Il Summit County Court of Common Pleas di Akron è diventato un focolaio di contenzioso sull’amianto, schierando migliaia di richieste presentate contro Johns Manville da lavoratori affetti da cancro ai polmoni o altre malattie legate all’amianto o, poiché molti sono morti, dai loro eredi. Dal 2015, più di 2.000 di questi casi sono stati risolti, i ricorrenti hanno pagato da un fondo fiduciario nazionale da 80 milioni di dollari istituito da Travellers, il più grande assicuratore di Johns Manville. Ma gli importi della liquidazione sono stati modesti: a partire da $ 800 e raramente più di $ 20.000, ha affermato Thomas W. Bevan, un avvocato con sede a Hudson, Ohio.

“La vergogna è che le famiglie aspettano molto tempo per una piccola quantità di denaro”, ha affermato il giudice Elinore Marsh Stormer, giudice di Common Pleas. “Vuoi vedere giustizia fatta. E non so che aspettare 20 anni per 1.200 dollari sia giustizia”.

Johns Manville ha dichiarato bancarotta nel 1982 per evitare quella che ha chiamato “responsabilità tremenda” dalla corsa delle azioni legali dopo che l’amministrazione per la sicurezza e la salute sul lavoro, nota come OSHA, ha iniziato a regolamentare l’amianto. I querelanti hanno inseguito gli assicuratori della società in seguito al deposito del Capitolo 11; il tribunale fallimentare ha approvato un accordo multimilionario con Travellers nel 1986. Johns Manville è emerso dal capitolo 11 nel 1988, ma quasi tre decenni di contenzioso sono continuati. Alcuni querelanti successivi non inclusi nell’accordo del 1986 hanno accusato i viaggiatori di travisare Johns Manville e la propria conoscenza dei rischi dell’amianto.

Legato da appelli, il caso alla fine è arrivato alla Corte Suprema degli Stati Uniti nel 2009. I giudici hanno rinviato il caso a una corte d’appello, che nel 2014 ha ripristinato una sentenza di fallimento secondo cui i viaggiatori pagano accordi transattivi e interessi per un totale di $ 500 milioni.

“Questo è stato un caso estremamente insolito”, ha detto Bevan, che si è fatto le ossa come impiegato legale in un contenzioso sull’amianto nel 1989, assistendo un mentore con azioni legali contro le aziende di gomma che nessuno voleva accettare a causa della loro difficoltà. Nel suo primo caso dopo la scuola di giurisprudenza all’inizio degli anni ’90, ha rappresentato un dipendente Goodyear con cancro ai polmoni che era stato esposto all’amianto.

“La posizione iniziale era una negazione completa e totale, come se si trattasse di una sorta di bufala o truffa”, ha detto di Goodyear. Un avvocato dell’azienda, ha detto Bevan, “ha battuto il pugno sul tavolo e ha detto: ‘Siamo un’azienda di pneumatici; non usiamo amianto!’ … Avevano un reparto di amianto lì a Goodyear. Ne ho delle foto.

“Mi hanno riso in faccia, letteralmente”, ha detto Bevan. “Hanno garantito che avrebbero vinto la causa. … Dopo un processo di due settimane e mezzo e hanno perso, erano tipo: ‘Aspetta un minuto. Abbiamo un problema qui.’”

Bevan, i cui genitori hanno lavorato brevemente presso aziende di pneumatici, ha detto che uno dei 15.000 casi di amianto più tristi gestiti dalla sua azienda ha coinvolto un elettricista Goodyear in pensione che ha venduto tutto per acquistare una barca per navigare in Florida e nei Caraibi. “Quello è stato il suo sogno per molti anni, poi ha iniziato ad avere questi problemi respiratori”. Aveva il mesotelioma, un tumore aggressivo correlato all’amianto che può colpire i tessuti che rivestono l’addome, i polmoni, il cuore o i testicoli. Dopo la sua diagnosi, ha venduto la sua barca e ha noleggiato una roulotte in Florida.

“Sono andato a incontrarlo prima di fare una deposizione”, ha detto Bevan. “Questo ragazzo grande, forte, orgoglioso e alto era proprio come uno scheletro. Il cancro era così grave che doveva urinare ogni 10 minuti circa. Aveva un Porta Potty proprio lì nella roulotte vicino alla sedia su cui era seduto. Si è scusato in anticipo perché i farmaci e il cancro lo stavano colpendo. Ha detto: ‘Spero che non ti dispiaccia.'”

“Dopo un paio d’ore, non ce l’avrebbe fatta e si è urinato addosso”, ha ricordato Bevan. “Potresti vedere lo sguardo sul suo viso: l’umiliazione e l’imbarazzo e ciò che questa malattia gli aveva fatto”.

Nel suo contenzioso, Bevan ha utilizzato le foto che avevano accompagnato l’articolo principale in un numero del 1964 della newsletter di Goodyear, in occasione del 50 ° anniversario della divisione prodotti industriali amianto dell’azienda. Le foto mostrano lavoratori senza protezione respiratoria che manipolano l’amianto, dalla raffinazione della fibra nel bidone di carico all’arrotolamento di fogli di amianto per la spedizione.

Gli ex dipendenti delle aziende di gomma di Akron descrivono l’amianto che galleggia all’interno delle piante come fiocchi di neve e che ricopre la pelle e i vestiti con polvere bianca.

L’amianto era nell’intonaco che Nathan J. Manson ha usato per realizzare stampi per pneumatici a Goodyear dal 1976 al 2005. Manson, che ha anche servito come supervisore, ha sviluppato problemi respiratori durante quel periodo e gli è stata diagnosticata una broncopneumopatia cronica ostruttiva, nota come BPCO , circa 10 anni dopo essere andato in pensione. Non ha tentato di citare in giudizio Goodyear, anche se crede che le sue condizioni siano legate al suo lavoro lì.

“Ora che sto invecchiando, la mia BPCO sta peggiorando”, dice Manson, che ha bisogno di ossigeno due volte al giorno, usa inalatori e ha avuto un ictus tre anni fa. Il 77enne amava pescare sul lago Erie, ma ha finito per vendere la sua barca. Anche se coltiva ancora fagiolini, zucchine, zinnie e soprattutto calendule nel suo giardino, “Dico a tutti che lavoro per cinque minuti; poi devo sedermi per 15”.

La connessione del benzene

A partire dal 1934, Goodyear iniziò a produrre Pliofilm, una plastica gommata utilizzata per proteggere attrezzature e armi, nonché per avvolgere cibo e droghe, negli stabilimenti di Akron e St. Mary’s, Ohio. I lavoratori usavano il benzene, un solvente legato per la prima volta alla leucemia e ad altri tumori del sangue alla fine degli anni ’40, nel processo di produzione.

Peter Infante, allora giovane epidemiologo dell’Istituto nazionale per la sicurezza e la salute sul lavoro, o NIOSH, è stato tra i primi a individuare il rischio per i lavoratori Pliofilm. Il suo primo studio, pubblicato nel 1977, ha mostrato un aumento da cinque a dieci volte del rischio di leucemia tra i lavoratori fortemente esposti al benzene dal 1940 attraverso follow-up sul loro stato nel 1975.

Immediatamente dopo la pubblicazione dello studio, l’OSHA ha affermato che avrebbe preso in considerazione uno standard temporaneo di emergenza per il benzene, inasprindo il limite di esposizione da 10 parti per milione a 1 ppm, ritenuto il livello più basso possibile. Marvin J. Sakol, un ematologo Akron presente nello studio, ha testimoniato all’udienza sul benzene dell’OSHA a Washington il 20 luglio 1977.

Sakol aveva curato un certo numero di dipendenti della gomma, diagnosticando nove dei 120 lavoratori Pliofilm con eritroleucemia acuta, o sindrome di Di Guglielmo, una rara forma di cancro. “Mi sono insospettito perché lavoravano tutti nello stesso dipartimento”, ha testimoniato Sakol. “Nove persone non possono ottenere Di Guglielmo su 120 a meno che non ci sia qualcosa nell’ambiente, nell’ambiente di lavoro, nel farlo”.

Quando ha iniziato a fare domande, ha detto Sakol, il direttore medico di Goodyear gli ha detto “di non scherzare e non erano affari miei”. La società ha negato all’epoca che i lavoratori della Pliofilm fossero stati esposti al benzene.

Quando l’OSHA si è trasferita per rendere permanente lo standard di benzene da 1 ppm nel 1978, è stata citata in giudizio dall’American Petroleum Institute e da altri gruppi industriali che hanno affermato che il numero era irraggiungibile e avrebbe paralizzato gli affari. Nel 1980, la Corte Suprema degli Stati Uniti si è pronunciata a loro favore, affermando che il governo non aveva dimostrato che il limite del benzene doveva essere abbassato. Solo nel 1987 il limite di 1 ppm è entrato in vigore.

Infante, che ha lavorato presso NIOSH e poi OSHA prima di diventare un esperto di controversie legali, afferma che lo standard è obsoleto. “Gli europei raccomandano un limite di esposizione al benzene di 0,05 ppm, 20 volte inferiore a quello degli Stati Uniti”, ha sottolineato.

Decenni di prove

“L’industria della gomma era piena di agenti cancerogeni”, ha affermato Hefner, il leader sindacale locale. “Sapevano che il benzene faceva male. Sapevano che l’amianto era dannoso. Voglio dire, queste aziende non sono stupide, ma si sono rifiutate di fare qualsiasi cosa al riguardo”.

Ad esempio, negli atti pubblicati del 28 ° Congresso nazionale sulla sicurezza nel 1939 , il medico di Goodyear, il dottor PA Davis, scrisse delle “polveri nell’industria della gomma”, comprese le condizioni polmonari come l’asbestosi e la silicosi. Davis ha riconosciuto che “tutte le polveri sono dannose per il sistema umano nel suo insieme quando le concentrazioni sono sufficientemente elevate”.

Infante ha affermato che tali prove sono disponibili per le aziende da più di un secolo in alcuni casi, citando una ricerca svedese del 1897 sull’associazione tra benzene e malattie del sangue.

“Abbiamo avuto i primi casi di leucemia segnalati nel 1928 in Italia”, ha detto. “Le aziende avevano informazioni, direi, negli anni ’50”.

Ad esempio, la Shell era a conoscenza della connessione tra benzene e leucemia attraverso un rapporto del 1943 preparato per l’azienda e una nota del 1950 di un consulente.

“I lavoratori morivano non solo di anemia aplastica, o di ciò che chiamiamo pre-leucemia, ma morivano anche di leucemia. E [le società] si sono semplicemente sedute su di esso; non volevano influenzare i loro affari”, ha detto Infante. “E poi quando i lavoratori si ammalavano di leucemia, lo negavano, perché non volevano che il pubblico lo sapesse”.

Sebbene molte cose siano cambiate, le note aziendali interne e altri documenti risalenti all’inizio del 1900 indicano che le aziende di tutto l’ecosistema della gomma non solo erano consapevoli dei pericoli di varie sostanze chimiche, come l’amianto e il benzene, ma che alcune tentarono anche di nascondere il rischio che queste sostanze poste, come ha indicato Sakol nella sua testimonianza sugli esami del sangue che i suoi pazienti affetti da leucemia hanno ricevuto negli impianti di gomma.

“Quando abbiamo fatto la visita in loco nel ’76, alcuni membri del nostro staff ci hanno fatto notare che alcune cartelle per i lavoratori della Pliofilm erano vuote e all’epoca sembravano sospette”, ha ricordato Infante.

Alla Babcock & Wilcox, che forniva a molte aziende della gomma caldaie e altri prodotti contenenti amianto, un promemoria tra otto dirigenti nel 1978 suggeriva di correggere silenziosamente le violazioni nel suo negozio di elettrodi ma di non pubblicare segnali di avvertimento o notificare ai dipendenti e all’OSHA l’eccesso di polvere di “sospetti cancerogeni [come] amianto, polvere di ferro, farina di silice e altri”.

“L’indagine sarà gestita nel modo più discreto possibile”, affermava la nota. “È una preoccupazione dei partecipanti alla riunione che un problema di lavoro come uno sciopero o una citazione OSHA per non conformità sarebbe imminente se la forza lavoro oraria fosse consapevole dell’apparente pericolo di esposizione all’amianto”.

BWX Technologies Inc. e Babcock, la sua ex società madre, hanno entrambi rifiutato di commentare il memo.

Ma in tutto il settore, i lavoratori si erano già resi conto che qualcosa non andava. I leader sindacali hanno negoziato con sei grandi aziende della gomma per finanziare studi sulla salute sull’ambiente di lavoro negli anni ’70 che hanno portato a una ricerca fondamentale dell’Università di Harvard e dell’Università della Carolina del Nord . “C’era consenso tra il sindacato e le aziende sul fatto che i membri stavano contraendo e morendo di cancro a un tasso piuttosto elevato”, ha affermato David Goldsmith, un epidemiologo della George Washington University che faceva parte del team di ricerca dell’UNC e in seguito ha condotto uno studio sul cancro alla prostata tra i lavoratori della gomma.

“Entrambe le parti sapevano che si trattava di un problema grave”, ha detto Goldsmith. “C’è stato chiaramente un incontro di menti che in altri contesti avrebbe potuto spingere il sindacato e le aziende in direzioni opposte”. Con l’accesso ai registri aziendali, sindacali e di morte, i ricercatori sono stati in grado di studiare lavori specifici e le loro esposizioni chimiche. Hanno diagnosticato malattie tra i lavoratori di quelle aree.

Bevan, l’avvocato querelante, ha affermato che le persone che non lavoravano negli stabilimenti hanno anche affrontato esposizioni dannose, casi che sono più difficili da vincere. “Alcune persone hanno avuto l’esposizione perché un membro della famiglia l’ha portata a casa sui loro vestiti”, ha detto. I residui chimici possono accumularsi anche sui capelli dei lavoratori, sotto le unghie o nei pori.

Diversi studi medici hanno associato cancro, condizioni respiratorie, problemi neurologici e malattie autoimmuni con esposizioni da portare a casa e ambientali, che vanno dall’amianto e dal benzene alle neurotossine che colpiscono il cervello e agli interferenti endocrini come il piombo che interrompono lo sviluppo neurologico nei bambini . Alcune sostanze chimiche vengono anche trasmesse geneticamente o attraverso l’esposizione transplacentare. “Per le donne incinte esposte al benzene, i loro figli hanno un rischio maggiore di sviluppare la leucemia”, ha detto Infante.

“C’era consenso tra il sindacato e le aziende sul fatto che i membri stavano contraendo e morendo di cancro a un ritmo piuttosto alto”.

DAVID GOLDSMITH, EPIDEMIOLOGO DELLA GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY

La vedova di uno dei pazienti di Sakol ha sviluppato eritroleucemia dopo aver lavato la tuta satura di benzene del marito notte dopo notte per almeno due decenni. Ha combattuto sette anni per assicurarsi il risarcimento dei lavoratori per la morte del marito, ed è morta meno di un anno dopo, ha detto Infante. “Non è mai stata in grado di ottenere alcun rimedio per la sua stessa malattia”.

Una coppia, che viveva ai margini dell’Industrial Excess Landfill , un sito di Superfund a Uniontown, Ohio, si è accordata in via extragiudiziale con le parti potenzialmente responsabili dopo che il loro figlio di 21 anni è morto di cancro alle ossa. La gomma e altre aziende hanno scaricato tonnellate di rifiuti solidi e liquidi nella discarica. La US Environmental Protection Agency ha recentemente avviato un’indagine sulla contaminazione delle acque sotterranee nell’area.

Sebbene molti lavoratori della gomma e residenti abbiano chiesto un risarcimento per le malattie associate ai prodotti chimici industriali, un numero incalcolabile di persone non ci ha provato, o non gli è mai passato per la mente.

Dawn Kupris Phifer sospettava un legame dell’industria della gomma con il cancro e altre malattie subite da parenti e compagni di classe nel corso degli anni. Phifer è cresciuto a Goodyear Heights, un quartiere industriale. Suo padre, suo nonno, suo fratello, due sorelle e suo figlio avevano tutti il cancro. Alcuni membri della famiglia e amici hanno respinto le sue preoccupazioni o le hanno detto che era negativa, ha detto. Questo non è insolito dato il forte orgoglio cittadino e la nostalgia per i giorni di Rubber City.

Anche la famiglia di Norma James non ha mai preso in considerazione alcuna azione legale per i loro disturbi. Suo padre lavorava alla Goodyear e le fu diagnosticato un cancro ai polmoni e alla prostata. Sua madre aveva un cancro all’utero. Suo zio, un dipendente Goodyear che viveva a meno di un miglio dalla sede dell’azienda, aveva un cancro alla prostata e sua moglie aveva un cancro al cervello.

James, che ha l’asma, ha detto che suo padre di solito faceva la doccia allo stabilimento. Quando indossava i suoi abiti da lavoro a casa, li toglieva in garage. “Ha parlato di lavarsi le mani e di usare acetone e benzene per pulirsi”, ha detto. “I medici in seguito hanno affermato che gli anni in cui ha fatto ciò avrebbero potuto contribuire al suo cancro”.

Preston Andrews sospetta che l’esposizione sproporzionata al nero lampada, al benzene e all’amianto abbia avuto un ruolo nella morte di suo padre, un dipendente Goodrich, e di uno zio, un lavoratore di Firestone. L’anziano Andrews e i suoi fratelli sono cresciuti in un minuscolo villaggio della Louisiana e sono emigrati uno per uno in un condominio vicino a Goodyear, a East Akron, negli anni ’40, quando la voce si è sparsa di opportunità nelle fabbriche di gomma e una fuga da forme più dure di razzismo in il profondo sud. Come in altri settori, gli afroamericani sono stati relegati in “ghetti occupazionali” nei lavori meno pagati, più sporchi e più pericolosi: lavoro nella parte anteriore della produzione che li esponeva quotidianamente a una quota maggiore di sostanze chimiche tossiche, che si aggrappavano ai loro vestiti e diffondersi alle loro famiglie.

“ Quando mio padre e loro hanno iniziato, lavoravano praticamente nella stanza del mulino”, ha detto Andrews, descrivendo le attività che mescolavano gomma grezza con nero lampada e altre sostanze chimiche. “Non potevano costruire pneumatici”. Andrews, che ha lavorato presso BF Goodrich dal 1966 fino a quando non è stato ridimensionato nel 1981, crede che avrebbe potuto cavarsela meglio dei suoi anziani, perché ha trascorso solo due anni nella stanza del mulino dopo che suo padre lo ha aiutato a trovare un lavoro nella stanza dei tubi.

“Era chiaro che c’erano modelli di lavoro specifici”, ha detto Goldsmith, l’epidemiologo, dei risultati della ricerca dell’UNC e di Harvard. “Gli uomini afroamericani hanno iniziato a fare i lavori più sporchi come la miscelazione e la miscelazione”.

Manson, che era attivo nel sindacato, ha detto che le opportunità e le condizioni hanno iniziato a migliorare quando lui e Andrews si sono stabiliti come lavoratori della gomma, il risultato della pressione sindacale, della legislazione sui diritti civili e dei regolamenti industriali. La paga è aumentata nella sala del mulino, ha detto, e il pool di lavoratori è diventato più integrato.

“Il negozio di gomma ha iniziato a fare ammenda e ad allentarsi perché non volevano scioperi e scioperi a tavolino”, ha aggiunto Andrews. “Avevano bisogno della fornitura di pneumatici”.

Rimedi attraverso i regolamenti

Il fiume Cuyahoga – inquinato dai rifiuti di gomma che scorrevano a nord di Akron, dai veleni dell’industria di Cleveland e da automobili, pneumatici e materassi scaricati lì – ha preso fuoco più di una dozzina di volte prima dell’approvazione del Clean Water Act nel 1972. È diventato un simbolo di crescente ambientalismo in un contesto di deindustrializzazione. Un crescente interesse per la salute e l’ambiente iniziato negli anni ’60 è culminato in una raffica di nuove agenzie di regolamentazione e regolamenti negli anni ’70.

I lavoratori e il pubblico hanno visto miglioramenti graduali, anche se il cambiamento è arrivato troppo lentamente per molti, inclusi il padre e il nonno di Gary Clark, entrambi morti di cancro ai polmoni e hanno lavorato in aziende di pneumatici. Clark, che si unì a suo padre alla Goodrich alla fine degli anni ’70 e vi lavorò per sette anni, ha beneficiato di più dispositivi di protezione e condizioni più sicure secondo le nuove leggi.

Ma non poteva sfuggire alla lampada nera, che filtrava dai suoi pori, irritando la sua pelle e macchiando le lenzuola. Clark ha detto che gli ci è voluto un mese per adattarsi all’intensità della puzza di zolfo: “Quell’odore è di 100 volte una volta che entri nella pianta”.

Le leggi stesse non erano prive di difetti. Ad esempio, il Toxic Substances Control Act , noto come TSCA, non copriva decine di migliaia di sostanze chimiche legacy che erano automaticamente ritenute conformi ai requisiti di test. Meno di una dozzina di sostanze chimiche sono state vietate dalla TSCA da quando è entrata in vigore nel 1976.

Solo nel 2019 l’EPA ha annunciato che avrebbe avviato le valutazioni del rischio di amianto , tricloroetilene (TCE) , 1,3-butadiene e formaldeide , che sono stati tutti utilizzati nell’industria della gomma.

L’OSHA, da parte sua, non è stata in grado di tenere il passo con l’eccesso di sostanze chimiche pericolose sul posto di lavoro. In una dichiarazione pubblica insolitamente schietta nel 2013, l’allora leader dell’agenzia, David Michaels, ha dichiarato : “Non c’è dubbio che molti degli standard chimici dell’OSHA non siano adeguatamente protettivi”. Di conseguenza, ha affermato l’OSHA, “decine di migliaia di lavoratori si ammalano o muoiono” a causa dell’esposizione chimica.

“Non c’è dubbio che molti degli standard chimici dell’OSHA non siano adeguatamente protettivi”.

DAVID MICHAELS, ALLORA CAPO DELL’OSHA

Gli ambientalisti sono cautamente ottimisti riguardo al futuro sotto l’amministrazione Biden, che si è mossa per aumentare la responsabilità aziendale per le pulizie di Superfund e ridurre l’arretrato, tra le altre iniziative.

“Dovremo aspettare probabilmente circa 24 mesi in questa amministrazione per vedere se sono davvero seri”, ha affermato Mustafa Santiago Ali, vicepresidente per la giustizia ambientale, il clima e la rivitalizzazione della comunità presso la National Wildlife Federation. Ali ha trascorso 24 anni con l’EPA, di recente come consulente senior per la giustizia ambientale e il rilancio della comunità.

La strada davanti

Ad Akron, gli stabilimenti di gomma rimanenti sono molto più sicuri rispetto agli anni passati, anche se più piccoli con la fine della produzione di pneumatici per passeggeri tra il 1975 e il 1982. Sia Goodyear che Firestone producono ancora pneumatici da corsa a Rubber City.

A livello aziendale, Goodyear ha sperimentato materiali rinnovabili come l’olio di soia, che ha sostituito il petrolio in alcune delle sue recenti linee di pneumatici, nonché sostituzioni del nero lampada. La società madre di Firestone utilizza il nero lampada recuperato da pneumatici riciclati per ridurre le emissioni di carbonio.

Le classifiche complessive di Goodyear, il più grande produttore di pneumatici al mondo, sono migliorate rispetto alle liste Toxic 100 pubblicate dal Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) dell’Università del Massachusetts ad Amherst. Goodyear è ora al 71 ° posto nell’indice Toxic 100 Air Polluters del 2021 , in calo rispetto al 19 del 2008 . Bridgestone/Firestone, 81 anni nel 2008, era completamente fuori dalla lista l’anno scorso.

Ora che la maggior parte della produzione si è spostata a sud, ovest e oltremare, gli stabilimenti Akron rappresentano meno del 5% dei punteggi di tossicità delle loro società madri.

Ma i ritardi nel controllo delle emissioni all’interno e all’esterno degli impianti avranno conseguenze a lungo termine, ha affermato Stephen Markowitz, direttore del Barry Commoner Center for Health and the Environment del Queens College di New York, che si è consultato con NIOSH e l’EPA.

“Condizioni più sicure negli ultimi 10 anni non si rifletteranno sulla salute… per altri 20 o 30 anni”, ha affermato Markowitz, coautore di uno studio del 1991 che collega l’orto-toluidina al cancro della vescica presso la Goodyear Chemical alle Cascate del Niagara. E mentre la deindustrializzazione sta vomitando meno inquinamento dalle fabbriche, le sostanze chimiche tossiche del passato sono ovunque. “Molta contaminazione del suolo persiste davvero per anni e anni e persino decenni”, ha detto Markowitz. Se il terreno è disturbato, ad esempio da lavori edili o da bambini che giocano, quelle sostanze chimiche possono disperdersi nell’aria.

La via da seguire per i cittadini è diventare più istruiti sull’impatto sulla loro salute, spingere per la responsabilità aziendale, votare e migliorare le normative, le politiche e i finanziamenti a livello locale, statale e nazionale, ha affermato Ali.

“Dobbiamo assicurarci che ci sia maggiore trasparenza in tutti questi processi e nei sistemi”, ha affermato.

Akron sta lentamente tornando dal suo passato industriale, continuando i tentativi di diversificare la sua base economica, ripulire i simboli dell’inquinamento industriale come Summit Lake, onorare i lavoratori della gomma con un nuovo monumento nel centro e riqualificare le aree dismesse: le strutture vuote e la terra lasciata dalla gomma aziende.

Jason Segedy, direttore della pianificazione e dello sviluppo urbano della città, vede la riqualificazione delle aree dismesse come una vittoria che stimola la crescita economica e ripulisce le aree potenzialmente pericolose.

Akron aveva 75 siti dismessi in un inventario iniziale, secondo l’EPA. Due terzi dei siti fanno parte di tre progetti in aree con tassi di povertà e disoccupazione superiori alla media: Riverwalk, dove si trova la nuova sede di Goodyear; la Bridgestone Redevelopment Area, che comprende Firestone; e il Corridoio Biomedico, a sud di Goodyear ea est di Goodrich. Il vasto campus di Goodrich ora comprende un parco, un incubatore di imprese e una Spaghetti Warehouse.

Un piano per rivisitare Summit Lake ha catturato un’ampia attenzione. Alcuni residenti di Akron hanno bei ricordi del lago come destinazione turistica con un parco divertimenti, una sala da ballo, una pista di pattinaggio, una spiaggia e una piscina. Situato a circa due miglia dal centro, il lago naturale di 97 acri un tempo era una fonte di acqua potabile, ma alla fine è diventato così inquinato dai rifiuti industriali delle fabbriche di gomma e di altre aziende che la città ha smesso di usarlo a tale scopo e ha vietato di nuotare lì.

I leader della città si sono incontrati con i residenti della comunità a lungo trascurata di Summit Lake per sollecitare il loro contributo sui miglioramenti del vicinato e delle attività ricreative, aggiornarli sulla qualità dell’acqua e tentare di reprimere i problemi di gentrificazione. Nella vecchia casa delle pompe di Firestone ora c’è un centro naturalistico.

Summit Lake è il simbolo di quanto Akron sia diventato più pulito, ha affermato John A. Peck, professore presso il Dipartimento di Geoscienze dell’Università di Akron. Per molto tempo, il contenuto magnetico e di metalli pesanti dei sedimenti del lago è cresciuto insieme all’industria della gomma e alla popolazione della città.

“È salito alle stelle ed è rimasto alto per molto tempo”, ha detto Peck. Ogni anno che passa, i sedimenti più puliti seppelliscono i sedimenti contaminati, ma “sai di non scavare”.

“La cosa interessante per me di Summit Lake è che nel centro di un ambiente urbano, hai questo gioiello naturale”, ha detto Peck.

I ricordi dell’odore solforico delle ciminiere delle fabbriche attirano ancora dibattiti sul fatto che fosse l’odore del denaro e della prosperità o della malattia e della morte. Considerando i costi passati e futuri, ne è valsa la pena?

Non ci sono risposte semplici. Senza l’industria della gomma, hanno affermato i residenti dall’Europa, dagli Appalachi e dal profondo sud, non sarebbero chi sono o dove sono. Akron non sarebbe Akron.

Per il reverendo Kevin Goode, che spesso fa affidamento sui tubi dell’ossigeno per respirare, contare le sue benedizioni non significa che non abbia rimpianti.

“In retrospettiva, guardando indietro”, ha detto Goode, “probabilmente non avrei lavorato dove ho lavorato”.