Fonte:The Conversation

Peter Bloom, University of Essex

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has been widely condemned for its unjustified aggression. There are legitimate fears of a revived Russian empire and even a new world war. Less discussed is the almost half trillion dollar (£381 billion) defence industry supplying the weapons to both sides, and the substantial profits it will make as a result.

The conflict has already seen massive growth in defence spending. The EU announced it would buy and deliver €450 million (£375 million) of arms to the Ukraine, while the US has pledged US$350 million in military aid in addition to the over 90 tons of military supplies and US$650 million in the past year alone.

Put together, this has seen the US and Nato sending 17,000 anti-tank weapons and 2,000 Stinger anti-aircraft missiles, for instance. An international coalition of nations is also willingly arming the Ukrainian resistance, including the UK, Australia, Turkey and Canada.

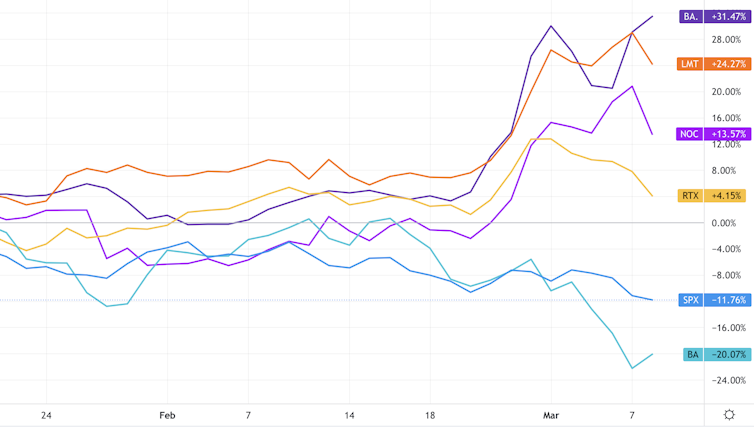

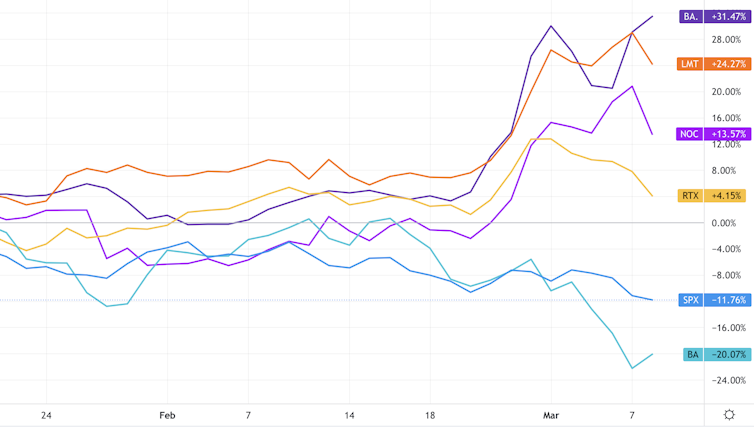

This is a major boon for the world’s largest defence contractors. To give just a couple of examples, Raytheon makes the Stinger missiles, and jointly with Lockheed Martin makes the Javelin anti-tank missiles being supplied by the likes of the US and Estonia. Both US groups, Lockheed and Raytheon shares are up by around 16% and 3% respectively since the invasion, against a 1% drop in the S&P 500, as you can see in the chart below.

BAE Systems, the largest player in the UK and Europe, is up 26%. Of the world’s top five contractors by revenue, only Boeing has dropped, due to its exposure to airlines among other reasons.

Defence company share prices vs S&P 500

Trading View

Opportunity knocks

Ahead of the conflict, top western arms companies were briefing investors about a likely boost to their profits. Gregory J. Hayes, the chief executive of US defence giant Raytheon, stated on a January 25 earnings call:

We just have to look to last week where we saw the drone attack in the UAE … And of course, the tensions in eastern Europe, the tensions in the South China Sea, all of those things are putting pressure on some of the defence spending over there. So I fully expect we’re going to see some benefit from it.

Even at that time, the global defence industry had been forecast to rise 7% in 2022. The biggest risk to investors, as explained by Richard Aboulafia, managing director of US defence consultancy AeroDynamic Advisory, is that “the whole thing is revealed to be a Russian house of cards and the threat dissipates”.

With no signs of that happening, defence companies are benefiting in several ways. As well as directly selling arms to the warring sides and supplying other countries that are donating arms to Ukraine, they are going to see extra demand from nations such as Germany and Denmark who have said they will raise their defence spending.

The overall industry is global in scope. The US is easily the world leader, with 37% of all arms sales from 2016-20. Next comes Russia with 20%, followed by France (8%), Germany (6%) and China (5%).

Beyond the top five exporters are also many other potential beneficiaries in this war. Turkey defied Russian warnings and insisted on supplying Ukraine with weapons including hi-tech drones – a major boon to its own defence industry, which supplies nearly 1% of the world market.

And with Israel enjoying around 3% of global sales, one of its newspapers recently ran an article that proclaimed: “An Early Winner of Russia’s Invasion: Israel’s Defense Industry.”

As for Russia, it has been building up its own industry as a response to western sanctions dating back to 2014. The government instituted a massive import substitution programme to reduce its reliance on foreign weaponry and expertise, as well as to increase foreign sales. There have been some instances of continued licensing of arms, such as from the UK to Russia worth an estimated £3.7 million, but this ended in 2021.

As the second biggest arms exporter, Russia has targeted a range of international clients. Its arms exports did fall 22% between 2016-2020, but this was mainly due to a 53% reduction in sales to India. At the same time, it dramatically enhanced its sales to countries such as China, Algeria and Egypt.

According to a US congressional budget report: “Russian weaponry may be less expensive and easier to operate and maintain relative to western systems.” The largest Russian defence firms are the missile manufacturer Almaz-Antey (sales volume US$6.6 billion), United Aircraft Corp (US$4.6 billion) and United Shipbuilding Corp (US$4.5 billion).

What should be done

In the face of Putin’s imperialism, there are limits to what can be achieved. There appears little credible possibility for Ukraine to demilitarise in the face of Russia’s continued threat.

There have nevertheless been some efforts to de-escalate the situation, with Nato, for example, very publicly rejecting the request of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky to establish a no fly zone. But these efforts are undermined by the huge financial incentives on both sides for increasing the level of weaponry.

What the west and Russia share is a profound military industrial complex. They both rely on, enable and are influenced by their massive weapons industries. This has been reinforced by newer hi-tech offensive capabilities from drones to sophisticated AI-guided autonomous weapons systems.

If the ultimate goal is de-escalation and sustainable peace, there is a need for a serious process of attacking the economic root causes of this military aggression. I welcomed the recent announcement by President Joe Biden that the US will directly sanction the Russian defence industry, making it harder for them to obtain raw materials and sell their wares internationally to reinvest in more military equipment.

Having said that, this may create a commercial opportunity for western contractors. It could leave a temporary vacuum for US and European companies to gain a further competitive advantage, resulting in an expansion of the global arms race and creating an even greater business incentive for new conflicts.

In the aftermath of this war, we should explore ways of limiting the power and influence of this industry. This could include international agreements to limit the sale of specific weapons, multilateral support for countries that commit to reducing their defence industry, and sanctioning arms companies that appear to be lobbying for increased military spending. More fundamentally, it would involve supporting movements that challenge the further development of military capabilities.

Clearly there is no easy answer and it will not happen overnight, but it is imperative for us to recognise as an international community that long-lasting peace is impossible without eliminating as much as possible the making and selling of weapons as a lucrative economic industry.![]()

Peter Bloom, Professor of Management, University of Essex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Traduzione automatizzata dell’articolo tramite google translator. Il riferimento rimane l’articolo in lingua inglese.

Ucraina: i colossi mondiali della difesa guadagnano tranquillamente miliardi dalla guerra

L’invasione russa dell’Ucraina è stata ampiamente condannata per la sua ingiustificata aggressione. Ci sono legittime paure di un impero russo rianimato e persino di una nuova guerra mondiale. Meno discusso è l’industria della difesa di quasi mezzo trilione di dollari (381 miliardi di sterline) che fornisce le armi a entrambe le parti e i notevoli profitti che ne deriveranno.

Il conflitto ha già visto una crescita massiccia della spesa per la difesa. L’UE ha annunciato che acquisterà e consegnerà 450 milioni di euro (375 milioni di sterline) di armi all’Ucraina, mentre gli Stati Uniti hanno impegnato 350 milioni di dollari in aiuti militari oltre alle oltre 90 tonnellate di rifornimenti militari e 650 milioni di dollari in passato solo anno.

Messo insieme, questo ha visto gli Stati Uniti e la Nato inviare 17.000 armi anticarro e 2.000 missili antiaerei Stinger, per esempio. Una coalizione internazionale di nazioni sta anche armando volentieri la resistenza ucraina, inclusi Regno Unito, Australia, Turchia e Canada.

Questo è un grande vantaggio per i più grandi appaltatori della difesa del mondo. Per fare solo un paio di esempi, Raytheon produce i missili Stinger e, insieme alla Lockheed Martin, i missili anticarro Javelin forniti da artisti del calibro di Stati Uniti ed Estonia. Entrambi i gruppi statunitensi, le azioni Lockheed e Raytheon, sono aumentate rispettivamente del 16% e del 3% circa dall’invasione, contro un calo dell’1% nell’S&P 500, come puoi vedere nel grafico sottostante.

BAE Systems, il più grande operatore nel Regno Unito e in Europa, è in aumento del 26%. Dei primi cinque appaltatori del mondo per fatturato, solo Boeing è diminuita, a causa della sua esposizione alle compagnie aeree , tra gli altri motivi .

Prezzi delle azioni delle società di difesa rispetto all’S&P 500

L’occasione bussa

Prima del conflitto, le principali compagnie di armi occidentali stavano informando gli investitori su un probabile aumento dei loro profitti. Gregory J. Hayes, l’amministratore delegato del gigante della difesa statunitense Raytheon, ha dichiarato in una richiesta di guadagni del 25 gennaio :

Non ci resta che guardare alla scorsa settimana dove abbiamo visto l’attacco dei droni negli Emirati Arabi Uniti… E, naturalmente, le tensioni nell’Europa orientale, le tensioni nel Mar Cinese Meridionale, tutte queste cose stanno mettendo sotto pressione alcune delle spese per la difesa. là. Quindi mi aspetto pienamente che ne vedremo dei benefici.

Anche a quel tempo, si prevedeva che l’industria globale della difesa aumenterà del 7% nel 2022. Il rischio più grande per gli investitori, come spiegato da Richard Aboulafia, amministratore delegato della società di consulenza per la difesa statunitense AeroDynamic Advisory, è che “l’intera faccenda si rivela essere un castello di carte russo e la minaccia svanisce”.

Senza alcun segno che ciò accada, le compagnie di difesa stanno beneficiando in diversi modi. Oltre a vendere direttamente armi alle parti in guerra e fornire altri paesi che stanno donando armi all’Ucraina, vedranno una domanda aggiuntiva da nazioni come Germania e Danimarca che hanno affermato che aumenteranno le loro spese per la difesa.

L’intero settore è di portata globale . Gli Stati Uniti sono facilmente il leader mondiale, con il 37% di tutte le vendite di armi dal 2016 al 2020. Segue la Russia con il 20%, seguita da Francia (8%), Germania (6%) e Cina (5%).

Oltre ai primi cinque esportatori ci sono anche molti altri potenziali beneficiari di questa guerra. La Turchia ha sfidato gli avvertimenti russi e ha insistito per fornire all’Ucraina armi, inclusi droni hi-tech , un grande vantaggio per la propria industria della difesa, che fornisce quasi l’1% del mercato mondiale.

E con Israele che gode di circa il 3% delle vendite globali, uno dei suoi giornali ha recentemente pubblicato un articolo che proclamava: “Un primo vincitore dell’invasione russa: l’industria della difesa israeliana”.

Per quanto riguarda la Russia, ha costruito la propria industria in risposta alle sanzioni occidentali risalenti al 2014. Il governo ha istituito un massiccio programma di sostituzione delle importazioni per ridurre la sua dipendenza da armi e competenze straniere, nonché per aumentare le vendite all’estero. Ci sono stati alcuni casi di licenza continua di armi, come dal Regno Unito alla Russia per un valore stimato di 3,7 milioni di sterline , ma questo è terminato nel 2021.

In quanto secondo esportatore di armi, la Russia ha preso di mira una serie di clienti internazionali. Le sue esportazioni di armi sono diminuite del 22% tra il 2016 e il 2020, ma ciò è dovuto principalmente a una riduzione del 53% delle vendite all’India. Allo stesso tempo, ha notevolmente migliorato le sue vendite in paesi come Cina, Algeria ed Egitto.

Secondo un rapporto sul bilancio del Congresso degli Stati Uniti: “Gli armamenti russi potrebbero essere meno costosi e più facili da usare e mantenere rispetto ai sistemi occidentali”. Le più grandi aziende di difesa russe sono il produttore di missili Almaz-Antey (volume delle vendite di 6,6 miliardi di dollari), United Aircraft Corp (4,6 miliardi di dollari) e United Shipbuilding Corp (4,5 miliardi di dollari).

Cosa dovrebbe essere fatto

Di fronte all’imperialismo di Putin, ci sono limiti a ciò che si può ottenere. Sembra che ci siano poche possibilità credibili per l’Ucraina di smilitarsi di fronte alla continua minaccia della Russia.

Ci sono stati tuttavia alcuni sforzi per ridurre l’escalation della situazione, con la Nato, ad esempio, che ha rifiutato pubblicamente la richiesta del presidente ucraino Volodymyr Zelensky di stabilire una no fly zone. Ma questi sforzi sono vanificati dagli enormi incentivi finanziari da entrambe le parti per aumentare il livello delle armi.

Ciò che l’Occidente e la Russia condividono è un profondo complesso industriale militare . Entrambi fanno affidamento, abilitano e sono influenzati dalle loro enormi industrie di armi. Ciò è stato rafforzato dalle nuove capacità offensive hi-tech, dai droni ai sofisticati sistemi d’arma autonomi guidati dall’intelligenza artificiale .

Se l’obiettivo finale è una riduzione dell’escalation e una pace sostenibile, è necessario un serio processo di attacco alle cause economiche profonde di questa aggressione militare. Ho accolto con favore il recente annuncio del presidente Joe Biden che gli Stati Uniti sanzionano direttamente l’industria della difesa russa, rendendo più difficile per loro ottenere materie prime e vendere le loro merci a livello internazionale per reinvestire in più equipaggiamento militare.

Detto questo, questo potrebbe creare un’opportunità commerciale per gli appaltatori occidentali. Potrebbe lasciare un vuoto temporaneo per le aziende statunitensi ed europee per ottenere un ulteriore vantaggio competitivo, con conseguente espansione della corsa agli armamenti globale e creando un incentivo commerciale ancora maggiore per nuovi conflitti.

All’indomani di questa guerra, dovremmo esplorare modi per limitare il potere e l’influenza di questa industria. Ciò potrebbe includere accordi internazionali per limitare la vendita di armi specifiche, supporto multilaterale ai paesi che si impegnano a ridurre la loro industria della difesa e sanzioni alle compagnie di armi che sembrano fare pressioni per aumentare la spesa militare. Più fondamentalmente, comporterebbe il supporto di movimenti che sfidano l’ulteriore sviluppo delle capacità militari.

Chiaramente non c’è una risposta facile e non accadrà dall’oggi al domani, ma è imperativo per noi riconoscere come comunità internazionale che una pace duratura è impossibile senza eliminare il più possibile la produzione e la vendita di armi come industria economica redditizia.