Fonte Theconversation.com

James Gaughan, University of York and Peter Sivey, University of York

On July 19 2021, nearly all legal restrictions aimed at limiting the spread of COVID-19 were removed in England. A requirement to isolate at the request of NHS Track and Trace remains for people exposed to an infected person and who aren’t double vaccinated, but other control measures such as the closure of nightclubs and limits on the size of indoor social gatherings have been lifted.

This move marked the end of the “roadmap” for gradually easing restrictions, which had been announced back in February. A major point stressed by politicians was that progress towards opening up again would be “irreversible”.

Yet following the relaxation of restrictions in the summer of 2020, control measures were ultimately reintroduced the following winter with national lockdowns in November 2020 and January 2021. So a natural question now is, will 2021 be any different?

Plateauing cases set to rise

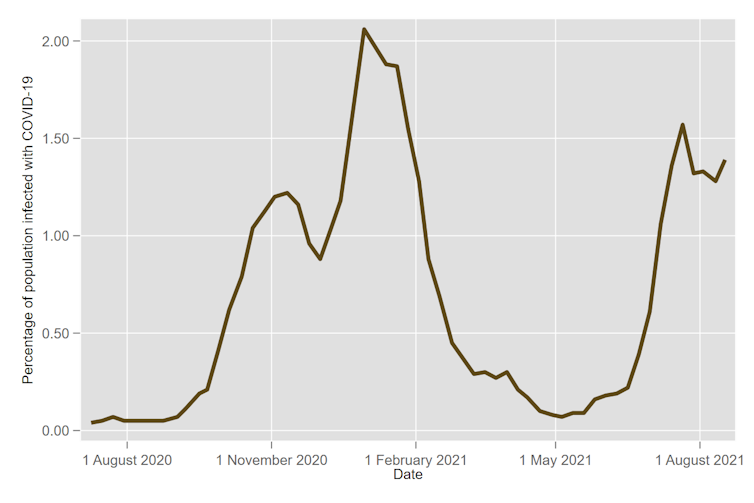

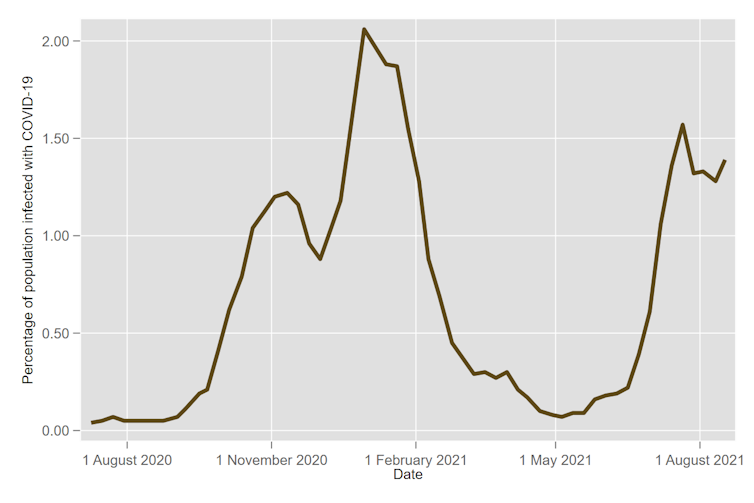

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) infection survey gives an estimate of the number of people infected with COVID-19 at any point in time by testing a representative sample of the population. Its estimates of the proportion of people infected in England over the last year are shown in the graph below.

ONS Infection Survey

Infections have risen from low levels in April and May this year to a peak of around 1.57% in July, shortly after restrictions were lifted. The rate of overall infection then fell to 1.28% in August and subsequently plateaued.

The drop and levelling off may be due, in part, to the school summer holidays, as previously noted. The risk now is that infection rates could rise again from their already high levels due to a gradual increase in social contact, including through schools returning and possibly from more parents and other adults returning to workplaces.

Fewer cases leading to hospitalisation

However, a crucial factor affecting pressure on the healthcare system – which is what drives restrictions – is how common COVID-19 is in different age groups. According to the ONS, between July 10 and August 20 2021, the estimated rate of infection in the community was highest among 17- to 24-year-olds (3.23%). This is more than double what it was between January 9 2021 to February 19 (1.53%), when overall infections in England were at their highest.

In contrast, the rate of infection in the 70+ age group is just over half its January-February rate (0.38% in July-August, 0.72% in January-February). This difference is important, since younger age groups are at a lower risk of hospitalisation.

Combining data on hospital admissions by age and population estimates, both published by the ONS, we can see that in the week ending February 21 2021, the number of people under 25 admitted to hospital with COVID-19 was just 0.2% of the total number of people in this age bracket estimated to have had the disease over the previous week. In contrast, admissions of over-25s represented around 4.2% of the estimated cases in the community for this group. This shows how much stronger the link between infection and hospitalisation is as age increases.

Additionally, the risk of hospitalisation has fallen substantially for older people since vaccines have been widely rolled out. In the week ending August 22 2021, the number of over-25s admitted to hospital with COVID-19 represented only around 1.9% of the estimated number infected in this age group. So while rising infections in schools may translate to an increase in cases in older people, the impact on hospital admissions is likely to be lower than it would have been in pre-vaccine 2020.

Not on the road to lockdown?

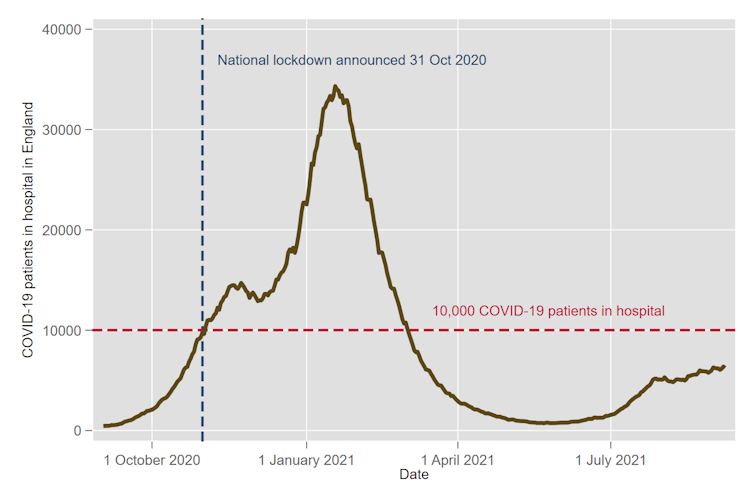

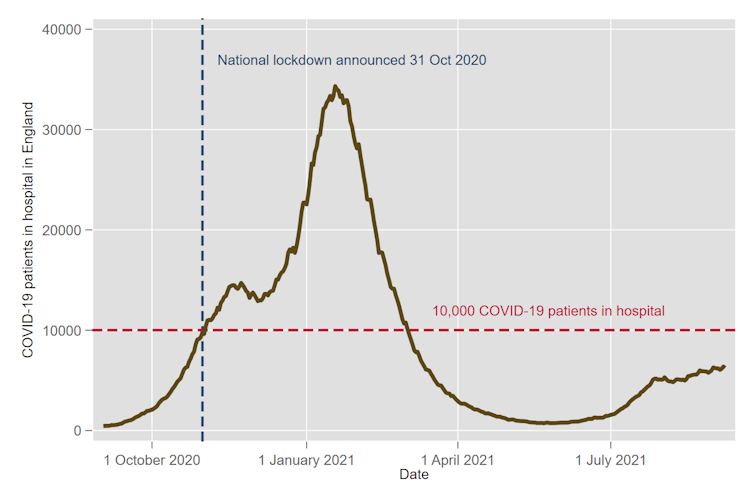

Throughout the pandemic, the need for restrictions has been driven by the number of patients in hospital with COVID-19. The graph below highlights the number of patients in hospital when the November 2020 lockdown was announced. At this point, on October 31 2020, the number of COVID-19 patients in hospital was just less than 10,000. Current patient numbers are over 6,000, having increased from less than 1,000 in May and June.

coronavirus.data.gov.uk

So can we think of the current situation as 60% on the way to lockdown? In some ways, yes. With around 10,000 patients in hospital with COVID-19, in October 2020 the pressure on the health system was judged severe enough to justify a national lockdown. However, the rate of upward trend is also key.

Two weeks after the start of this lockdown, numbers in hospital had reached just under 14,000 (restrictions take around two weeks to start bringing hospitalisations down). If we were to get to the same level in the coming months, it would likely be with a much slower upward trajectory than in 2020. While rising, the current rate of increase of hospital patients is not similar to the sort of rapid exponential growth seen just prior to previous lockdowns.

The critical difference between late summer 2020 and late summer 2021 is the successful rollout of the vaccination programme. Around 89% of people aged 16+ in England have received a first dose of vaccine and around 80% a second dose. The latest surveillance report by Public Health England indicates that against the dominant delta variant of COVID-19, two doses of a vaccine provide 79% protection against experiencing symptoms and, most critically, 96% protection against hospitalisation.

The same report indicates that from mid-July to mid-August, 97.5% of the entire English population had antibodies for COVID-19 either from previous infection or vaccination. This all suggests the vaccination programme has substantially weakened the link between cases and hospitalisation, not so much by preventing infection completely but protecting against hospitalisation in the vast majority of cases. One remaining uncertainty is to what extent protection offered by vaccines wanes. A booster programme to combat this is still to be finalised by the government.

The coming winter will inevitably bring more cases of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, and hospital numbers for COVID-19 are already high. However, mass vaccination has changed the prognosis. There is unlikely to be the same rapid increase in hospitalisations as seen previously. Some return of more minor restrictions in the winter is possible if hospital numbers continue to rise, but a full national lockdown remains unlikely.![]()

James Gaughan, Research Fellow in Health Economics, University of York and Peter Sivey, Reader in Health Economics, Centre for Health Economics, University of York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Postiamo questa traduzione svolta con google translator per facilitare la lettura dell’articolo. Il testo cui fare riferimento resta il testo originale in lingua inglese. editor

COVID-19 : improbabili ulteriori blocchi ma alcune restrizioni invernali sono possibili

James Gaughan, University of York and Peter Sivey, University of York

Il 19 luglio 2021, in Inghilterra sono state rimosse quasi tutte le restrizioni legali volte a limitare la diffusione del COVID-19 . Resta l’obbligo di isolare su richiesta del NHS Track and Trace per le persone esposte a una persona infetta e che non sono state vaccinate due volte, ma sono state revocate altre misure di controllo come la chiusura dei locali notturni e i limiti alle dimensioni degli incontri sociali al chiuso .

Questa mossa ha segnato la fine della “tabella di marcia” per un graduale allentamento delle restrizioni, che era stata annunciata a febbraio. Un punto importante sottolineato dai politici è che i progressi verso la riapertura sarebbero ” irreversibili “.

Tuttavia, in seguito all’allentamento delle restrizioni nell’estate del 2020, le misure di controllo sono state infine reintrodotte l’inverno successivo con i blocchi nazionali a novembre 2020 e gennaio 2021. Quindi una domanda naturale ora è: il 2021 sarà diverso?

Casi di plateau destinati a salire

L’ indagine sulle infezioni dell’Office for National Statistics (ONS) fornisce una stima del numero di persone infette da COVID-19 in qualsiasi momento testando un campione rappresentativo della popolazione. Le sue stime della percentuale di persone infette in Inghilterra nell’ultimo anno sono mostrate nel grafico sottostante.

Ricevi aggiornamenti sul coronavirus da esperti di salute

Le infezioni sono aumentate dai bassi livelli di aprile e maggio di quest’anno a un picco di circa l’1,57% a luglio, poco dopo la revoca delle restrizioni. Il tasso di infezione complessivo è poi sceso all’1,28% ad agosto e successivamente si è stabilizzato.

Il calo e il livellamento potrebbero essere dovuti, in parte, alle vacanze scolastiche estive, come già osservato . Il rischio ora è che i tassi di infezione possano aumentare di nuovo dai loro livelli già elevati a causa di un graduale aumento dei contatti sociali, anche attraverso il ritorno delle scuole e possibilmente da un maggior numero di genitori e altri adulti che tornano ai luoghi di lavoro.

Meno casi che portano al ricovero in ospedale

Tuttavia, un fattore cruciale che influenza la pressione sul sistema sanitario – che è ciò che guida le restrizioni – è quanto sia comune il COVID-19 nelle diverse fasce di età. Secondo l’ONS , tra il 10 luglio e il 20 agosto 2021, il tasso di infezione stimato nella comunità è stato più alto tra i 17 ei 24 anni (3,23%). Questo è più del doppio di quello che era tra il 9 gennaio 2021 e il 19 febbraio (1,53%), quando le infezioni complessive in Inghilterra erano al loro massimo.

Al contrario, il tasso di infezione nella fascia di età superiore ai 70 anni è poco più della metà del tasso gennaio-febbraio (0,38% in luglio-agosto, 0,72% in gennaio-febbraio). Questa differenza è importante, poiché le fasce di età più giovani sono a minor rischio di ricovero.

Combinando i dati sui ricoveri ospedalieri per età e le stime della popolazione , entrambi pubblicati dall’ONS, possiamo vedere che nella settimana terminata il 21 febbraio 2021, il numero di persone sotto i 25 anni ricoverate in ospedale con COVID-19 era appena lo 0,2% del numero totale di persone in questa fascia di età si stima che abbia avuto la malattia nella settimana precedente. Al contrario, i ricoveri degli over 25 hanno rappresentato circa il 4,2% dei casi stimati nella comunità per questo gruppo. Ciò dimostra quanto sia più forte il legame tra infezione e ricovero in ospedale con l’aumentare dell’età.

Inoltre, il rischio di ospedalizzazione è diminuito sostanzialmente per le persone anziane da quando i vaccini sono stati ampiamente diffusi. Nella settimana terminata il 22 agosto 2021, il numero di over 25 ricoverati in ospedale con COVID-19 ha rappresentato solo l’1,9% circa del numero stimato di infetti in questa fascia di età. Quindi, mentre l’aumento delle infezioni nelle scuole può tradursi in un aumento dei casi nelle persone anziane, è probabile che l’impatto sui ricoveri ospedalieri sia inferiore a quello che sarebbe stato nel pre-vaccino 2020.

Non sei sulla strada del lockdown?

Durante tutta la pandemia, la necessità di restrizioni è stata guidata dal numero di pazienti ricoverati in ospedale con COVID-19. Il grafico seguente evidenzia il numero di pazienti in ospedale quando è stato annunciato il blocco di novembre 2020. A questo punto, il 31 ottobre 2020, il numero di pazienti COVID-19 ricoverati in ospedale era di poco inferiore a 10.000. Gli attuali numeri di pazienti sono oltre 6.000, essendo aumentati da meno di 1.000 a maggio e giugno.

Quindi possiamo pensare alla situazione attuale come il 60% sulla strada per il blocco? In qualche modo sì. Con circa 10.000 pazienti ricoverati in ospedale con COVID-19, nell’ottobre 2020 la pressione sul sistema sanitario è stata giudicata abbastanza grave da giustificare un blocco nazionale. Tuttavia, anche il tasso di tendenza al rialzo è fondamentale.

Due settimane dopo l’inizio di questo blocco, i numeri in ospedale avevano raggiunto poco meno di 14.000 (le restrizioni impiegano circa due settimane per iniziare a ridurre i ricoveri). Se dovessimo raggiungere lo stesso livello nei prossimi mesi, sarebbe probabilmente con una traiettoria ascendente molto più lenta rispetto al 2020. Sebbene in aumento, l’attuale tasso di aumento dei pazienti ospedalieri non è simile al tipo di rapida crescita esponenziale osservata poco prima dei blocchi precedenti.

La differenza fondamentale tra la fine dell’estate 2020 e la fine dell’estate 2021 è il successo del programma di vaccinazione. Circa l’89% delle persone di età superiore ai 16 anni in Inghilterra ha ricevuto una prima dose di vaccino e circa l’80% una seconda dose. L’ultimo rapporto di sorveglianza di Public Health England indica che contro la variante delta dominante di COVID-19, due dosi di un vaccino forniscono una protezione del 79% contro i sintomi e, soprattutto, una protezione del 96% contro il ricovero in ospedale.

Lo stesso rapporto indica che da metà luglio a metà agosto, il 97,5% dell’intera popolazione inglese aveva anticorpi per COVID-19 da precedenti infezioni o vaccinazioni. Tutto ciò suggerisce che il programma di vaccinazione ha sostanzialmente indebolito il legame tra casi e ricovero, non tanto prevenendo completamente l’infezione ma proteggendo dall’ospedalizzazione nella stragrande maggioranza dei casi. Un’altra incertezza è fino a che punto la protezione offerta dai vaccini diminuisce. Un programma di sostegno per combattere questo problema deve ancora essere finalizzato dal governo.

Il prossimo inverno porterà inevitabilmente più casi di COVID-19 e altre malattie infettive e i numeri degli ospedali per COVID-19 sono già alti. Tuttavia, la vaccinazione di massa ha cambiato la prognosi. È improbabile che ci sia lo stesso rapido aumento dei ricoveri come visto in precedenza. Un ritorno di restrizioni più minori in inverno è possibile se il numero degli ospedali continua ad aumentare, ma rimane improbabile un blocco nazionale completo.